Our History & Buildings

Our History

Cambridge was a small town, a long carriage and ferry ride from Boston, when in 1759 the Church of England members who lived there petitioned Canterbury for a mission right in Cambridge. Appeal granted, the Reverend East Apthorp, a recent graduate of Jesus College at Cambridge, England, was appointed missionary. He supervised the building of the church designed by Peter Harrison, architect of the King’s Chapel in Boston, and ministered to its congregation for three years before leaving the hot revolutionary climate for England.

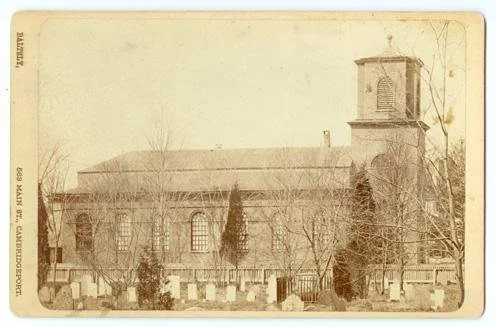

Commemorative stereoview celebrating the 3rd of July Celebration of Washington’s taking command of the American Army.

(Courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Society)

The interior was still incomplete when the Reverend Winwood Serjeant and many of his flock fled north and to England in the summer of 1774. During the American Bicentennial, John Coolidge, a parishioner, wrote of Christ Church:

Commemorative stereoview celebrating the 3rd of July Celebration of Washington’s taking command of the American Army. (Courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Society)

Although Continental troops had been billeted in the church, Martha Washington requested a service be held on Sunday 31 December 1775. Colonel Palfrey read the service and prayed that the King might be enlightened. But the Revolution rolled on and the church was closed until 1790. Not until 1829 were there funds to support a rector.

By 1857 the congregation flourishing under the Reverend Nicholas Hoppin was so large that the church was lengthened by two bays. While the Reverend James Field Spalding was rector, the organ was moved and the interior was redecorated in the latest fashion: cherubim and seraphim adorned the dark red and green walls. It was the Reverend Spalding who, on his arrival in 1879, discharged the most famous Sunday School teacher at Christ Church, Theodore Roosevelt, because he remained Dutch Reformed rather than becoming an Episcopalian! This is a curious footnote to the history of a church now well known for the ecumenical interests of its recent rectors and the very diverse backgrounds of its congregation.

In 1860, the tower bell was replaced with thirteen bells known as the Harvard Chime. They were given by Harvard alumni, including author Richard Henry Dana Jr., who donated royalties from his book Two Years Before the Mast. In 1883, the church was redecorated in the latest high Victorian fashion, which remained until 1920, when it was redone in Colonial colors.

In the century since, the church has continued to grow both physically and spiritually. The buildings and ministries offered by Christ Church have expanded to address the needs and concerns of the times. Christ Church has been integral in promoting social justice, civil rights, gender equality, LGBTQ inclusion, education, peace, and ministry to the hungry and homeless. The music ministry has grown to include two choirs, currently led by our Director of Music, David Carrier, and accompanied by a Schoenstein organ. Christian Education grew to include all ages from preschool through adulthood. In 2010, a successful capital campaign enabled the community to restore the church’s exterior and relocate the organ to a more central position. Our history continues to inform our present, even as we change and grow to better address our future.

“Hardly more than a shell when the Tories departed, it was battered during the Revolution, sympathetically restored in the Age of Jackson, extended just before the Civil War, and redecorated first during the presidency of General Grant and again during that of Herbert Hoover. Each generation has contributed something to this singularly unencumbered whole.”

Legacies of Slavery

Learning and Telling the Truth of Our History and Working to Repair the Harms

Christ Church Cambridge was founded in 1759, before slavery was abolished in Massachusetts (1783) and more than a century before the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery nationwide. A long-accepted historical narrative holds that New England was in the vanguard of the anti-slavery movement and its residents owned very few slaves and had little involvement with the slave trade or the slavery-related economy. It turns out that much of this narrative is untrue for New England in general and for Christ Church in particular. Christ Church was one of many New England churches, institutions, and individuals with connections to slavery. Most of the church’s founders and early members profited from the sin of slavery and its related enterprises. Indeed, most white New Englanders benefited in some fashion and to some degree from the slavery economy. However, Christ Church’s connections to slavery have only become widely recognized by our current parish community since 2021.

In October 2021, Alden Fossett, a Kellogg Fellow at Harvard’s Episcopal Chaplaincy, preached a sermon about Darby Vassall. He was a person formerly enslaved by John Vassall, among Christ Church’s founders, and George Read, an early member. Darby Vassall was, pursuant to his own request but for unknown reasons, buried in the Henry Vassall family tomb directly under our sanctuary. Following his emancipation in 1783, Darby Vassall went on to become a leader of the free Black community in Boston, a founder of the African Society and an advocate for the abolition of slavery and the education of Black children. His burial occurred on October 15, 1861, coincidentally during the centennial observance of the church’s first service. In December 2023, the City of Cambridge renamed the Vassal Lane Upper School for Darby Vassall.

Research undertaken by several Harvard students and Christ Church parishioners has revealed that Darby Vassall and his parents, Tony and Cuba, were but three of hundreds of persons enslaved by founders, benefactors, and early members of Christ Church. These included not only the intermarried Vassall and Royall families (the latter a major benefactor of Harvard University), but also the Borlands, Faneuils, Lechmeres, Lees, Olivers, Ruggleses, Sewalls, Temples, and Trollets. Rev. Winwood Serjeant, an early rector, was also an enslaver, as was Provincial Governor and parishioner William Shirley. Most of the slaves owned by these early Christ Church families, especially the Royalls and Vassalls, were held on Caribbean sugar plantations. All of these families and others also enslaved people as house servants in Cambridge and nearby towns. Moreover, other Christ Church families that may not have themselves enslaved people, were deeply involved in, and profited from the slave trade and related trade in sugar, molasses, rum, and other commodities. These families all gave money and in-kind gifts to the church. Based on research completed to date, it is safe to say that the construction and early growth of Christ Church were substantially based on proceeds from the labor of enslaved people. The precise figures will emerge as research continues.

While slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in 1783, the slavery-related profits of New Englanders and Christ Church members did not end then. The international slave trade was legal under U.S. law until 1808 and New England was a center of the cotton textile industry, which relied on cotton produced by enslaved people in the South, until the outbreak of the Civil War. Prominent members and benefactors of Christ Church were major profiters from the textile industry.

Abolitionists such as Richard Henry Dana were parishioners during the Antebellum period of the 19th century. Members and clergy, including particularly successive Rectors Gardner Day, Murray Kenney, and Robert Tobin were deeply involved in civil rights and antiwar movements. In 1967 the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at Christ Church to launch a summer of actions against the Vietnam War. In an early “reparations” initiative in 1970-1976, a “Committee of Whites” raised $100,000 from the parish, which was turned over to a “Committee of Blacks” to disburse as it saw fit, with no strings attached. An Anti-Racism committee was active at Christ Church during the 1990s but fell fallow in the early 2000s, only to be revitalized as the Racial Justice Group in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. This group is at work on anti-racism training and education, ongoing historical research, partnerships with other faith communities and local institutions, diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging initiatives, and advocating for racial and social justice legislative efforts.

Christ Church’s official histories, monuments, memorials, and historical displays are being revised to acknowledge Christ Church’s full and truthful history. A start was made in 2022 with the “Here Lies Darby Vassall” project. This was a multi-media installation commemorating Darby Vassall’s life and death. Created by Nicole Piepenbrink of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, it is an 11-minute filmed pilgrimage to the tomb by descendants of Darby Vassall and Christ Church parishioners. The film acknowledges publicly Christ Church’s involvement with slavery and launched a reckoning with that history. Descendants of Darby Vassall endorsed and participated in development of the film, which was shown continuously on a large screen in front of the church every evening from October 12 (the date of Darby Vassall’s death in 1861) through All Saints Sunday, November 6, 2022. In early 2023, following the installation, Christ Church’s Vestry commissioned a Reparations Committee to investigate and recommend reparative actions for our parish’s connections to slavery and racism. Among the first actions of the Reparations Committee, in collaboration with the Racial Justice Group, are the enhancement of public-facing signage, displays, and literature to include these historical truths. In our reparations journey, Christ Church is collaborating with and learning from other faith communities, academic and community institutions in the Cambridge-Boston area, many of which have progressed further in this work.

Our Buildings & Grounds

Christ Church was designed in 1759 by Peter Harrison of Newport, Rhode Island, the colonies’ first well-known architect. The building has been altered since, but the integrity of Harrison’s original design has remained intact. Most noticeable today on entering the building are its pleasing proportions. The building, however, was first built two bays shorter, measuring 45 feet wide and 60 feet long. In 1857 when the church was lengthened, the chancel and one pair of columns were moved forward, and two additional windows and sets of columns were inserted. Close inspection of the newer columns shows slight variations in the carving from the earlier ones, as well as a smoother cast to the columns themselves. The originals were hand-hewn and bored to prevent warping; the later ones were made from ship’s masts.

When the church was opened in 1761 the columns rose straight from the floor and were topped by simple Doric capitals. The pulpit probably stood in the center aisle at the front of the church and the altar might have been a simple table or chest. The present altar and choir stalls date from a renovation in 2013. The original 44 pews were high-backed box pews, purchased by individual parishioners and furnished according to the taste of the owner. These were replaced by slip pews in the 1850s using much of the wood from the original ones. The organ loft at the rear of the church and its decorative carving date from when the church was built, although the first organ is long gone – a casualty of the Revolution.

In the mid-1820s when the church was repaired under the direction of architect Isaiah Rogers, the columns were redesigned and the Ionic capitals and entablature blocks were carved, as well as the complementary decorative pilasters on the walls.

No one knows exactly what the first inside lights looked like; the present crystal chandeliers were given to the church in 1935 by Francis Sayre, Jr., who would later serve as Dean of the National Cathedral. The baptismal font at the rear of the church was given in 1941.

The tower originally housed a single 1500 pound bell cast in England. The bell was recast in 1858 to become part of the 13 bell Harvard Chime, given by a group of Harvard students to celebrate the church’s first 100 years. One of the students, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., contributed the royalties of Two Years Before the Mast to the project.

In the vestibule of the church is the bullet hole said to date from 1778 when the church was ransacked. It is not certain, however, how the hole was actually put there.

Pictures from 1883 show Victorian decoration throughout the church: the altar moved to the apse, choir stalls filled the chancel in collegiate style, ornate gas lighting protruded from the columns, cherubs were painted on the barrel-vault ceiling, and an organ with diapered facade pipes was now located in a chamber to the right of the apse. In 1940 the colorful decoration was changed to gray and off-white, the pulpit was replaced, the chancel was extended, larger choir stalls were introduced, and a new organ with a plain facade of dummy pipes resided in the chamber.

In 2013 the Sanctuary and choir stalls traded places to provide an altar rail that is accessible without steps. The number of pews was reduced to facilitate movement and to provide a less cluttered liturgical space. The new altar rail was modeled on the old one, using the gallery as a visual balance, and the pulpit was rotated to provide access from the altar. The organ console was sunk below a screen behind the altar so that the choirs would have improved sightlines; the 2006 organ facade was inspired by the original 1762 gallery organ.

In 2020, the ground directly in front of the church was raised in order to make the entrance accessible to people of all abilities. Glass doors were put in the narthex so that the historic wooden doors can remain open and welcoming to all who pass by.